The Reality of a Dog’s Natural Passing with Lymphoma

When a dog receives a devastating lymphoma diagnosis, owners immediately face many difficult questions. Therefore, many people wonder, will a dog with lymphoma die naturally, or does euthanasia present a more compassionate choice?

This article navigates the complex path of canine lymphoma, detailing aggressive types like large cell lymphoma in dogs and other forms. Furthermore, we explore typical outcomes and answer the key question, how long can a dog live with lymphoma.

This includes a discussion on the life expectancy for dog with lymphoma on prednisone, which many consider. Consequently, understanding the entire scope of this illness, also called canine large cell lymphoma, becomes crucial for making the best decisions.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Canine Lymphoma: A Comprehensive Overview

- The Path of Lymphoma and Its Observable Symptoms

- In-Depth Diagnosis and Staging of the Disease

- Exploring Treatment Options and Their Expected Outcomes

- Vitaplus (Vidatox) as a Complementary Therapy

- Navigating the End-of-Life Journey with Compassion

Understanding Canine Lymphoma: A Comprehensive Overview

Lymphoma, or lymphosarcoma as it is sometimes called, stands as one of the most frequently diagnosed cancers in the canine world. It is a systemic disease, meaning it originates in and affects the white blood cells known as lymphocytes, which are the cornerstone of the body’s immune system.

These critical cells travel throughout the body via the bloodstream and the intricate lymphatic network. This widespread nature makes lymphoma a challenging condition to contain locally, as the cancer is essentially a moving target.

However, this very characteristic is what makes it exceptionally susceptible to chemotherapy, which also moves throughout the body to target and destroy these cancerous cells wherever they may be.

There are more than 30 distinct subtypes of this cancer, and their behavior and progression can vary dramatically. Some subtypes are highly aggressive, progressing at an alarming rate, while others are indolent and slow to progress.

The life expectancy for a dog with lymphoma on prednisone or other treatment protocols is highly dependent on a multitude of factors, including the specific type and the stage of the cancer at diagnosis.

At the very core of a dog’s immune system are its lymphocytes. The two main types, B-cells and T-cells, are responsible for a variety of critical functions, from producing antibodies to fighting off infections to directly attacking and destroying abnormal or cancerous cells.

When these cells become malignant, they cease performing their proper functions, which can lead to a severely compromised immune system, anemia, clotting issues, and even organ failure.

For many pet owners, the agonizing question of will a dog with lymphoma die naturally is intimately tied to how quickly and how severely these life-threatening complications can arise.

The Path of Lymphoma and Its Observable Symptoms

Because lymphoma is a systemic cancer, it is not a condition that can be effectively treated by surgical removal alone. For this reason, aggressive and swift medical intervention is almost always the recommended course of action.

If left untreated, the disease will progress with alarming speed, often leading to a rapid decline and death within just a few weeks. However, with the right medical protocols and dedicated care, many dogs can go on to enjoy a high quality of life for many months or even years beyond their initial diagnosis.

The most common and often first noticeable symptom of lymphoma is the presence of enlarged lymph nodes. These lumps feel firm and round, but are generally not painful to the touch.

You can easily feel for them in several accessible locations on your dog’s body, such as under the jaw, in front of the shoulders, in the armpits, in the groin, or behind the knees. When you discover these suspicious lumps, it is absolutely essential to seek immediate veterinary attention.

Other, more generalized and non-specific symptoms can also occur, including uncharacteristic lethargy, a poor or nonexistent appetite, unexplained weight loss, and gastrointestinal issues like vomiting and diarrhea.

If you discover a swollen lymph node on your pet, it may be the first clear sign of canine large cell lymphoma and should not be ignored.

If you are trying to understand how long can a dog live with lymphoma both with and without treatment, the contrast is stark. Without any treatment, the median survival time for most types of lymphoma is typically only about a month.

With aggressive, multi-agent chemotherapy, this can be extended to over a year, and some dogs can even live for two years or longer. This makes early detection and treatment a paramount factor in a pet’s ultimate prognosis and quality of life.

In-Depth Diagnosis and Staging of the Disease

When your veterinarian suspects lymphoma, they will conduct a comprehensive physical examination to check all of your dog’s accessible lymph nodes and look for other signs of systemic illness.

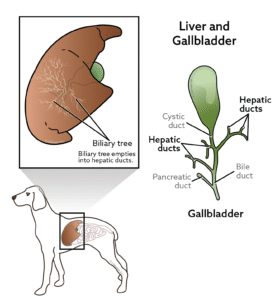

To confirm the diagnosis, they may recommend a series of diagnostic tests, including blood work, chest radiographs (x-rays), and an abdominal ultrasound.

A definitive diagnosis is most often made through a fine needle aspirate (FNA) or a surgical biopsy of an affected lymph node.

- Fine Needle Aspirate (FNA): A very tiny needle is used to collect a small sample of cells from the enlarged lymph node. This is a quick, easy, and relatively non-invasive procedure. The collected material is then placed on a slide and examined by a pathologist under a microscope to determine if the cells are cancerous.

- Biopsy: A small piece of the lymph node is surgically removed for a more detailed pathological analysis. While more expensive and invasive than an FNA, a biopsy provides more complete information and can help distinguish between the many different subtypes of lymphoma.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, your veterinarian or a veterinary oncologist will “stage” the cancer to determine its severity and how far it has spread throughout the body. This crucial process is vital for providing a more accurate prognosis and for creating a tailored treatment plan.

- Stage I: Only a single lymph node is involved.

- Stage II: Multiple lymph nodes are affected, but only on one side of the body.

- Stage III: Multiple lymph nodes are affected on both sides of the body.

- Stage IV: The cancer has spread to the liver and/or spleen.

- Stage V: Other organs, such as the bone marrow, skin, or gastrointestinal tract, are affected.

The substage is also a very important prognostic indicator: “A” indicates that the dog feels well at the time of diagnosis and shows no clinical signs, while “B” means the dog is already showing signs of feeling sick.

Dogs in substage A generally have a better prognosis and a more robust response to treatment, which is a key consideration when trying to understand how long can a dog live with lymphoma.

Exploring Treatment Options and Their Expected Outcomes

Chemotherapy is, without question, the most effective treatment for lymphoma in dogs. While a complete and permanent cure is exceedingly rare, the primary goal of treatment is to achieve remission, which means the cancer regresses and your dog’s quality of life is restored.

The good news is that most dogs tolerate chemotherapy remarkably well, often experiencing fewer and less severe side effects than humans do.

One of the most widely used and successful protocols is the University of Wisconsin CHOP Protocol. This multi-drug regimen is considered the gold standard and leads to complete remission in approximately 90% of dogs.

The median survival time with this protocol is 13-14 months. For those seeking a simpler approach, a single agent like doxorubicin can be used. Newer treatments, such as Tanovea and Laverdia, also offer promising alternatives with their own unique benefits and cost structures.

Prednisone, an oral steroid, is a relatively inexpensive and common medication used to help manage symptoms. It can provide a quick and significant improvement in a dog’s comfort and quality of life.

However, it is not a long-term solution and can make a dog’s cancer resistant to future, more effective chemotherapy drugs. A dog’s life expectancy for dog with lymphoma on prednisone alone is typically a short 2-3 months.

This is precisely why it is so crucial to consult with a veterinary oncologist before starting any steroid treatment if you are considering more aggressive therapies.

Vitaplus (Vidatox) as a Complementary Therapy

Complementary and alternative therapies are often a subject of great interest for pet owners facing a cancer diagnosis, and Vitaplus (Vidatox) is one such product.

The product, derived from the venom of the Cuban blue scorpion, is sold as a homeopathic remedy. Proponents of Vitaplus (Vidatox) highlight its supposed ability to reduce inflammation, manage pain, and even slow or stop tumor growth. They suggest its use as a supportive measure alongside conventional treatments or as a sole therapy for those who choose not to pursue chemotherapy.

The company that manufactures this product claims that it works by targeting specific ion channels involved in cellular signaling, which can affect the behavior of cancer cells.

They also promote it for its analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties, which could help improve a dog’s overall quality of life by providing relief from discomfort and reducing swelling in affected lymph nodes. Furthermore, the company asserts that it has anti-tumor properties, suggesting it can stop tumors from growing.

However, it is crucial for pet owners to approach these claims with caution. The scientific community has largely viewed Vitaplus (Vidatox) with skepticism.

The vast majority of the evidence supporting its use comes from anecdotal reports and testimonials rather than controlled clinical trials. In fact, some studies, particularly those on human hepatocellular carcinoma, have found that the product might actually increase tumor proliferation and invasion.

A few studies have investigated the potential for pain relief in human patients, but these findings have not been replicated in large-scale, peer-reviewed veterinary studies.

Because of the lack of robust scientific evidence, many conventional veterinary oncologists do not recommend its use. Without proper clinical trials, a veterinarian cannot accurately determine its effectiveness, safe dosage for a dog, or potential for harmful side effects.

Thus, while the idea of a natural remedy is appealing, owners should always prioritize evidence-based treatments and have an open, frank discussion with their vet about any complementary therapies they are considering. The goal is always to provide the most effective and safest care for the pet.

Navigating the End-of-Life Journey with Compassion

The question of will a dog with lymphoma die naturally is an incredibly difficult and painful one to face. As the disease progresses, the cancer cells will eventually develop resistance to all available treatments.

At this point, your dog will begin to feel very sick, showing signs of severe lethargy, a complete loss of appetite, and significant discomfort.

The lymph nodes will likely become very large and burdensome once again.

Allowing a dog with an aggressive cancer to die naturally often means they will endure a prolonged period of suffering.

They may experience unbearable pain, difficulty breathing, and a profound decline in their ability to perform even the simplest daily activities they once enjoyed. In these heartbreaking situations, most pet owners, in close consultation with their veterinarian, choose euthanasia as a final, compassionate act to prevent further suffering.

his decision is deeply personal, but it is often the kindest choice you can make when your dog’s quality of life is severely compromised. It is a way to ensure that your cherished companion can pass away peacefully and with dignity, surrounded by love.